The Supply Side of Inflation

By David Montgomery

As my self-imposed deadline for this article loomed, I started asking myself what I could write about the economy that would add value to that which anyone can read daily in the Wall Street Journal. Finally a topic my colleagues and I studied several years ago came to mind: the impact of regulation on the prices and the economy.

The Trump administration launched a major effort to cut down on new regulations and to revisit existing regulations to weed out those that did more harm than good. The Biden Administration has obliterated these gains with surge of new regulations and more to come. Those regulations are making it impossible for US industry to respond to the surge of demand coming from increased deficit spending and stimulus payments since 2021. When demand increases and supply is constrained, prices must rise. There will be no solution to inflation until the chains of regulation are loosened so as to permit supply to increase and meet demand.

The Trump administration made a successful and largely unheralded effort to restrain the issuance of new regulations and to redo or rescind existing regulations that had costs larger than their benefits. Unlike other initiatives that were pursued haphazardly or with inadequate leadership, the deregulation effort had clear objectives and an exceptionally well qualified staff to oversee the work.

President Trump issued an Executive Order with three key provisions:

- Establish a one-in/two-out policy for implementing new rules, to require removal of at least two rules for every new one issued;

- Implement a net freeze on net costs for regulation:

- Set up regulatory reform task forces to identify “outdated, unnecessary, or ineffective” regulations, those with costs greater than benefits, and those that inhibit jobs and job creation

This initiative actually worked, as the number of new rule makings for purposes other than rescinding previous regulations declined precipitously, and the 2 for 1 goal was greatly exceeded. The Trump Administration withdrew or delayed 860 regulations in its first 5 months. A great deal of the credit goes to a highly motivated and knowledgable Director and staff of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, the office within the Office of Management and Budget that oversees regulatory activity of all Executive agencies. The Biden Administration has left that office vacant.

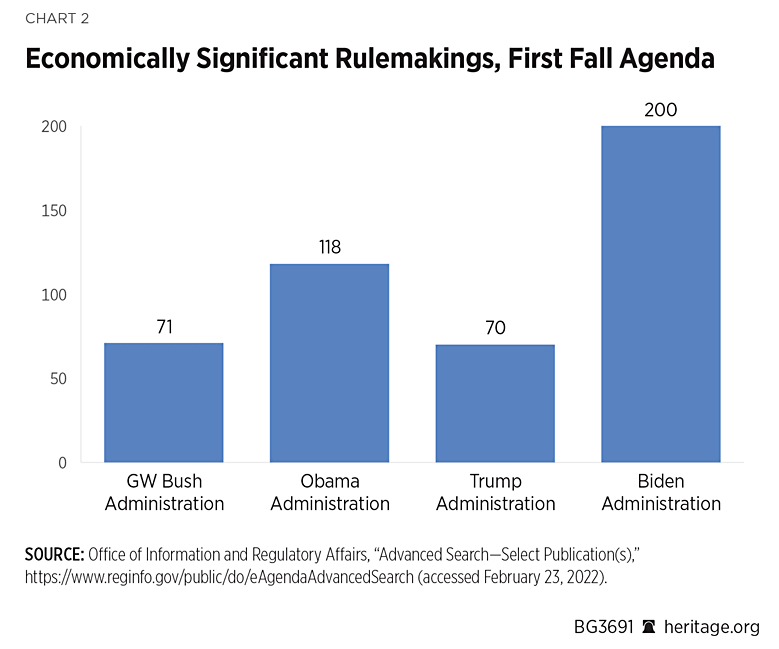

The Biden Administration has obliterated these gains with its surge of regulations surpassing even the record numbers of the Obama Administration. This can be seen clearly in the bar chart, in which the number of major regulations issued in each administration since George W Bush are plotted.

In reviewing this record in more detail, the Cato institute concluded that “compared to Obama, Biden is issuing more impactful rules with less oversight.”

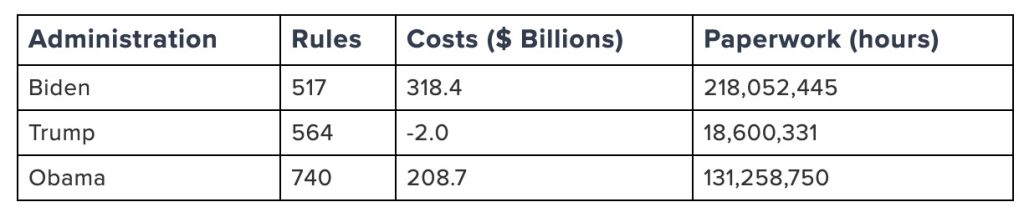

One pair of analysts estimated that the Biden regulatory agenda for the first year of his administration was equivalent to a tax increase of over $200 billion annually. Another estimated the cost through January 2023 at over $300 billion. As the table below shows, that exceeds even the Obama Administrations regulatory burden in its first two years, while the Trump Administration reduced the cost burden while reducing paperwork by over 90%.

These major regulations are just part of the problem, as regulatory dark matter is far more voluminous. As defined by the inventor of the term, regulatory dark matter is “reams of guidance documents consisting of general statements of policy and interpretive rules, as well as memoranda, interpretive bulletins, and other issuances—over the years that can carry regulatory weight.” This “stealth regulation” evades the review that is given to major regulations and skirts the requirements of the Administrative Procedures Act. These actions are taken on the initiative of individual bureaucrats, and can be highly restrictive or favorable to business depending on their bosses wishes.

Wayne Crews, an authority on the subject, lists several examples of such stealth regulation issued during the Obama Administration that “can have regulatory effect despite that being against the rules:”

- Waivers of statutory mandates contained within Obamacare itself via the administration’s unilateral extension of the employer mandate deadline, and the continuation of non-compliant health insurance policies;

- The Department of Justice/Education Department “Dear Colleague Letter on Transgender Students“;

- From the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, driverless car guidance, as well as “commonsense guidelines” on a “Driver Mode” for smartphones;

- The Department of Labor’s “administrator’s interpretations” on whether one is an independent contractor or an employee, and on franchising/joint employer status.

The last, from my own experience, has had a major effect on employment practices.

President Trump issued two Executive Orders that “significantly bolstered procedural safeguards… designed to curb the informal “guidance” that has often been issued by federal agencies to effectively implement binding policy requirements without following legally required notice and comment rulemaking procedures.” One of the first acts of the Biden Administration was to revoke these orders, as well as the 2 for 1 requirement for new regulations, thus reopening the floodgates.

Between the clear statistics on regulatory restraint in the Trump Administration and its harder-to-quantify efforts to control “stealth regulation,” I conclude that its regulatory reform efforts had a salutary effect on the American economy. Indeed, I can find no explanation for the remarkable growth of the economy during the Trump years that does not include tax and regulatory reform as major factors.

I directed a study at NERA Economic Consulting for the US Chamber of Commerce and another conservative organization that estimated just the annual costs of meeting greenhouse gas regulations planned by EPA prior to the Trump victory at $250 Billion by 2025 and $2.9 Trillion by 2040. That study included no other regulations. These regulations were put on hold by President Trump but are being resurrected by the Biden Administration. (My employer NERA was not happy when this study was mentioned by the President of the United States as the analysis he relied on in deciding to withdraw from the Paris Agreement that required these regulations.)

This then takes me to the impact that I think the Biden regulatory agenda is having on the economy. I have no quantitative studies to offer, as my former group at NERA is no longer allowed to do that kind of work. But the logic is eminently clear.

Almost all discussion of causes of inflation focuses on the errors of the Federal Reserve in waiting too long to end its policy of “quantitative easing” and the folly of passing one huge increase in deficit spending after another, long after any macroeconomic case could be made for additional stimulation to avoid recession. These might both be called “demand side” explanations of inflation.

There is also a “supply side” to consider. When increased incomes are earned due to increased productivity, that means that the economy is producing sufficient goods to satisfy the resulting increases in demand. This is the venerable “Say’s Law” of economics. That is not the case when the government hands out income by borrowing. In particular, during Covid lockdowns, the payments sent to all individuals were not associated with production of any additional goods. For a time, the mismatch between disposable income and available supply was hidden, because very little of those stimulus payments was actually spent.

Then the Biden Administration, with Republican help, passed another 1.7 Trillion in deficit spending. Together with the hoarded past stimulus payments, this set the stage for inflation. When the dam broke and the recipients of these windfalls went out to spend them, they found the shelves were bare. At that point consumers bid up the cost of available supplies of everything from bread to automobiles.

Under normal circumstances, rising prices would bring forth additional supply. Employers would hire back workers, invest in additional equipment, and increase production, and imports would flow toward the Unites States.

Unfortunately, the supply side was not normal. While massive deficit spending was increasing demand, the flood of new regulation raised costs, reduced willingness to invest and even discouraged workers from returning to work.

These regulatory constraints exacerbated the problems of supply chains inherited under Covid.

Ill-conceived decisions to shut down economic activity to combat Covid disrupted global supply chains and that effect, though waning, has lingered. The war in Ukraine and sanctions imposed on Russia reduce oil, natural gas and grain supply from that region.

Nevertheless, the United States remained the world’s largest economy and was, until 2021, the world’s largest producer of hydrocarbons. That put us in a position to replace a good bit of the lost supplies from the war in Ukraine, but the regulatory actions of the Biden Administration not only prevented increases but caused output of food and energy in the U.S to fall. Agricultural output has fallen steadily since 2020. In 2019 the Energy Information Administration projected that the US would produce about 5 billion barrels of crude oil in 2022, but we actually produced only 4 billion. Natural gas production also came in lower than forecasted in 2020, and that was with prices about 75% higher.

What these three sectors reveal — oil, natural gas and coal — is that rising food and energy prices have not produced any supply response. Indeed, while prices to producers of these necessities have risen, supply has actually fallen below past levels and expectations.

On the energy side, it has been the explicit policy of the Biden Administration to reduce U.S. production of oil and gas, despite its inevitable effect of raising prices and shifting production to unfriendly and unreliable sources. This was the Biden climate agenda, and it showed itself in the cancellation of the Keystone pipeline and other critical oil and gas infrastructure, a moratorium on leasing of federal lands, and slow-walking of drilling permits where leases were in place.

On the side of agricultural products, a study at Purdue University found a clear statistical correlation between increases in regulatory restrictions by EPA and USDA and reductions in farm productivity: “The long run effect is a -1.005% decline in productivity growth for a 1% increase in USDA regulation. EPA restrictions also have both a lagged and contemporaneous effect on productivity growth. The long-run effect indicates that a 1% increase in EPA regulation results in a -0.529% decline in productivity growth.”

For more concrete examples than this statistical association with the increase in regulatory activity, EPA is effectively banning the second most common agricultural herbicide, a key ingredient in maintaining farm productivity and particularly necessary for no-till corn farming on the Eastern Shore. The proposed resurrection of the Waters of the United States (WOTUS) regulation, killed during the Trump Administration, will saddle farmers with greatly increased costs and regulatory hurdles for using their own water supplies. The Labor Department also issues regulations affecting farm costs and productivity. From the combination of the three agencies (USDA, DOL and EPA) farm spokesmen expect increasing regulatory restrictions. Even the Biden Administration’s “regulatory freeze” was instituted for the purpose of retracting Trump-era pending regulations deemed too lenient.

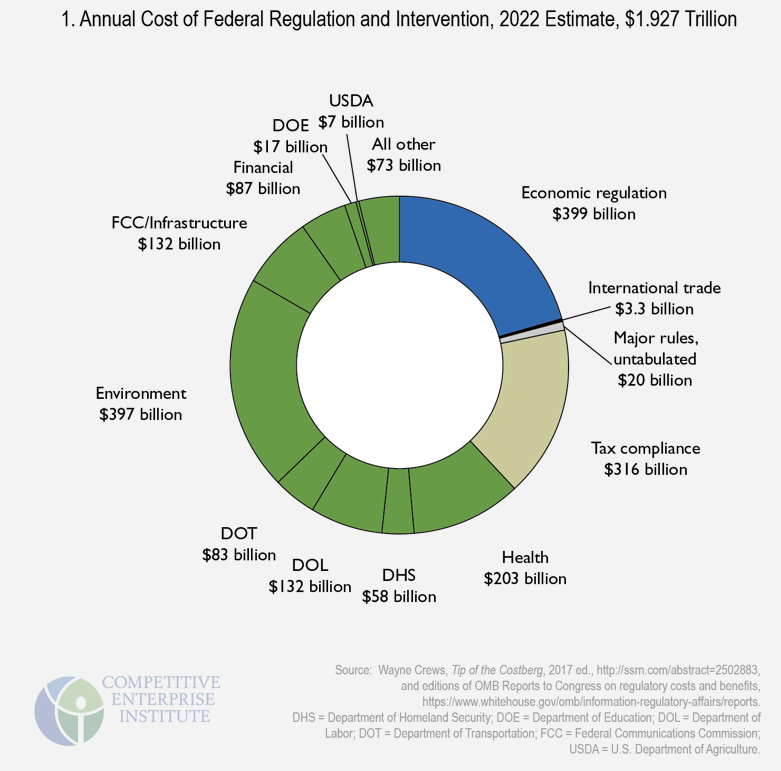

It is not energy and farming that alone suffer from increased regulatory restriction. Wayne Crews distributes the cost of regulation across agencies.

The Biden regulatory onslaught increases all these burdens, with two results:

- Increased costs that are passed on to consumers and show up as inflation that cannot be eliminated through monetary policy

- Lessened ability of businesses to ramp up production to satisfy the increased demand fueled by stimulus payments and other transfers

Thus we are left with another explanation of why prices are rising so rapidly, and some insight into what is needed to slow inflation. Monetary policy cannot control inflation that raised from a fundamental mismatch between current demand for goods fueled by deficit spending and the ability of the economy to produce those goods.

Worse yet, efforts of the Federal Reserve to reduce inflation by raising interest rates will indeed be likely to succeed in slowing the economy, but they will not reduce the amount of money in consumers hands to bid up the price of goods if deficits continue. This is a recipe for the stagflation of the 1970s, with a recession — sustained reductions in the production of goods and services — combined with high prices. Getting out of this bind clearly requires drastic reductions in the deficit to lessen the mismatch between demand and available supply

Even that will not be enough until the chains of regulation are loosened. Unfortunately, those who have looked at the regulatory agenda of this administration for 2023 and beyond see no such relief in sight. The State of the Union message laid out clearly a plan for two more years of increasing regulation. Only declining real incomes and rising prices can be the result.